PART 1: Christianity—Based on History

PART 2: The Need of Creed

PART 3: Hold to the Outline

Kyle Barton graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary with a Master of Divinity concentrating in Reformed Theology. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Systematic Theology at Baylor University focused on the relationship between ecclesiology and soteriology in the theologies of Augustine and Karl Barth.

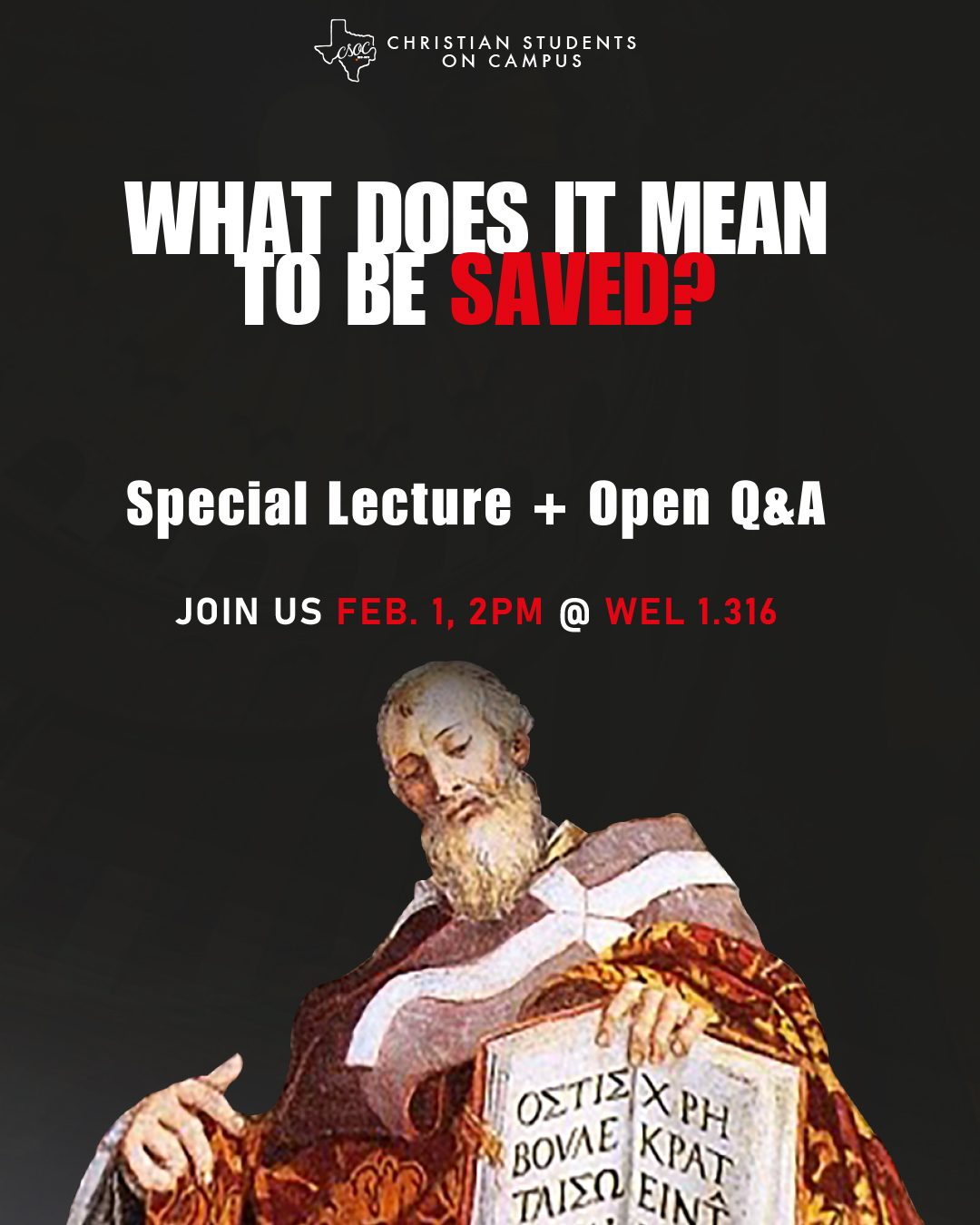

AT THE BEGINNING OF OUR THIRD BLOG POST on CSOC UT Austin’s Lecture Series, we’ll review two quotes from Swiss theologian Karl Barth. The first gives us a narrative view of the Christian faith and the second shows us the necessary response to the gospel. Guest lecturer Kyle Barton brought these engaging words to our attention in a special lecture hosted by CSOC in its seminar series: What Does it Mean to Be Saved by Jesus, and they are well worth revisiting as we continue our journey toward a deeper understanding of what it means to be saved.

Regarding faith, Karl Barth asserted that “for a Christian, ‘faith’ is faith in God, who in His inner life and nature is not dead, not passive, not inactive, but that God– the Holy Father, Son, and Spirit– exist in an inner relationship and movement, which may very well be described as a story, an event.”

And on the gospel: “What the gospel demands of human beings is more than notice, or understanding, or sympathy. It demands participation, comprehension, cooperation; it demands confession.”

As believers in Christ, Christian students, we chose to respond to the gospel, to actively participate in God’s story. Now our story and His have become eternally and irrevocably joined. Although we may not have realized it at the time of our confession, we were accepting and affirming God’s story by professing our belief in His story’s main character, Jesus Christ. While this assessment may seem to strip our salvation of its wonder and joy, it embraces a pragmatic truth. Our faith requires us to know Who Jesus Christ is. In his second letter to Timothy, Paul boldly declares, “I know Whom I have believed” (2 Tim. 1:12).

It’s easy to be dismissive of this fundamental requirement for the faith to be perpetuated because it just seems so obvious. But in its early life, the Christian faith had a potentially fatal encounter with a seemingly benign misconception. It’s not difficult to imagine the early believers in Christ, still enthralled by recent events, unintentionally misspeaking and miscommunicating the facts of Christ’s story. While this undoubtedly happened, it was relatively harmless as long as proper instruction prevailed. An example of this is even recorded in chapter 18 of Acts, where Priscilla and Aquila help Apollos, a powerful but errant preacher, understand the way of God more accurately (Acts 18:24-26).

This innocent instance, however, is a far cry from the situations that would arise only a few generations later. Misrepresentations of Christ were so prevalent even as early as A.D. 180, that Irenaeus, in his famous book “Against Heresies,” would address the issue with a poignant metaphor. He imagined the components of Christ’s story as separate tiles that formed a complete and beautiful mosaic of a king. But these same tiles, when incorrectly rearranged, could also form an image of a dog. A deceptive appropriator might then declare with conviction that the newly formed image was the king, the same king who had been the subject of the original mosaic. This unsettling thought experiment calls to mind Aaron’s heretical presentation of the golden calf to God’s people in Exodus 32: “This is your god, O Israel.” We are right to emphatically reject both declarations, but would we be able to discern one as readily as the other? As earnest believers in Jesus Christ, who desire to proclaim His gospel as part of the continuation of His story and ours, we would never intentionally misrepresent Who He is. But the ramifications of this precarious situation may leave us feeling unsettled and even paralyzed. As theologian Kevin Vanhoozer said, “Failure to identify the divine persons correctly leads to a misconstrual of the divine action, which in turn impedes our ability to participate in the divine story.”

By now the benefit, even the necessity, of a creed is obvious. But before creed comes outline. The word, “outline,” in Greek is derived, in part, from the Greek word meaning “the impression left from a strike.” The impression left after one thing has been sufficiently pressed into another captures the detail of the original object with faithful accuracy. The thought conveyed by the word “outline” is highly effective at presenting the ideal outcome of any exegetic communication from one person, or generation, to another. A faithful reproduction of the original. If the Christian faith depends on the accurate telling of the divine story, then the need for outline is clear.

The apostle Paul not only recognized this approach but employed this method with Timothy. In 2 Timothy 1:13, Paul tells Timothy to hold to the “outline” (various translations use “pattern” and “example” for this Greek word) of the healthy words that he had received from Paul. E. Kenneth Lee offers commentary on this passage in “New Testament Studies,” and notes the progression in how the gospel was conveyed. “What is more relevant is to recognize here one of those suggestive allusions in the New Testament to a definite form of belief framed upon some form of instruction for catechumens. In the very first Christian communities the impression made by the missionary preaching was given in a fixed form, and later deepened by systematic theological instruction. This passage would seem to refer to such a form of instruction.” In this way, outline is derived from and reinforces the original instruction.

Once you have the outline, the next step is confession; our reasonable response to the gospel’s demand. In light of our considerations on this topic, we may be enlightened to learn, but should not be surprised, that the literal translation of the Greek word for confession is “to speak the same thing.” We, who like Timothy, have “confessed the good confession,” heard the same story and proclamation, received the same instruction, and spoken the same thing (1 Tim 6:12).

We have believed in the same Jesus Christ, Who is our Savior. The historic pathway of the Christian faith is magnificent. It is awesome to realize that millions before us have traveled in the same steps, due in no small part to the faithful preservation of the events of Christ’s story as the gospel, through the development of its proclamation, instruction, and outline.

These steps may have continued to be sufficient for all time had the story not begun to stray by an erroneous retelling. Arius of Alexandria told a story of Jesus Christ, but the wrong story. As in Irenaeus’s mosaic example, he used the same details but arrived at a very different picture. One that would jeopardize participation in the gospel and salvation of Jesus Christ. The controversy attached to Arius’ name represents one of the most notable instances of “mosaic mismanagement” in history. The resulting storm of debate would spark fierce theological dispute, lead to multiple excommunications, and catalyze the inclusion of the most significant word in the Nicene Creed. One that would forever affirm Christ’s person and what it means to be saved. All this, in our future posts.