PART 1: Christianity—Based on History

PART 2: The Need of Creed

PART 3: Hold to the Outline

Kyle Barton graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary with a Master of Divinity concentrating in Reformed Theology. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Systematic Theology at Baylor University focused on the relationship between ecclesiology and soteriology in the theologies of Augustine and Karl Barth.

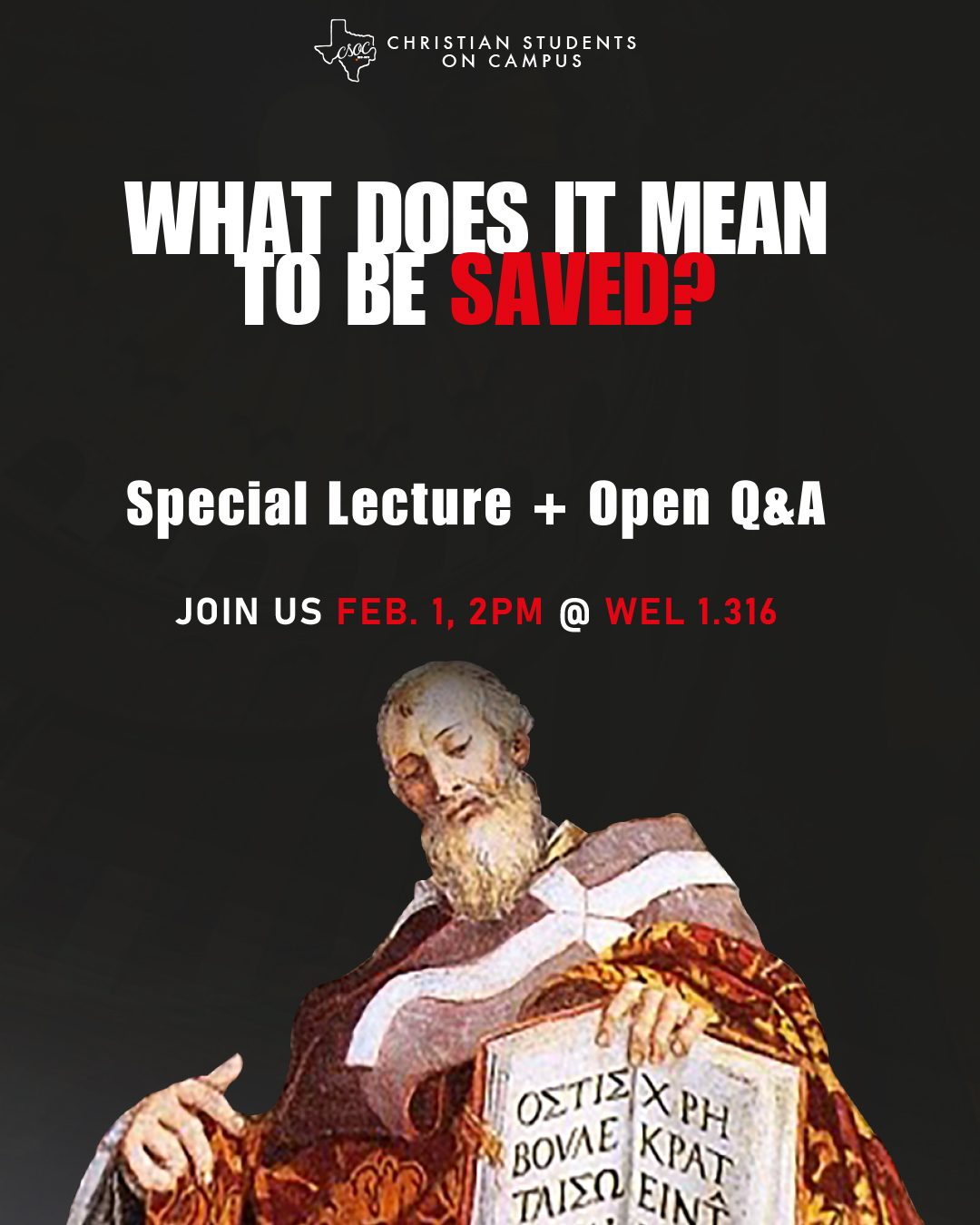

WE ENDED OUR LAST POST WITH AN EVENT that became news, which became good news, which became a proclamation. In this post, we’ll continue our journey toward one of the most important statements of Christian belief, the Nicene Creed of 325 AD. As Christianity grows increasingly diverse in practice and appearance, we who confess the good confession would benefit from a closer inspection of this fundamental Christian declaration. This is the second post in a four-part blog series as we recap highlights and insights from a special lecture hosted by CSOC in its seminar series: What Does it Mean to be Saved, with guest speaker Kyle Barton.

To help us understand the importance of the Nicene Creed, and perhaps shake us from a dismissive familiarity with its text, guest lecturer Kyle Barton was quick to introduce us to the words of JND Kelly. In his book, Early Christian Creeds, Kelly describes the Nicene Creed as “one of the few threads by which the tattered fragments of the divided robe of Christendom are held together.” At first reading, Kelly’s sentiment seems cynical, drawing attention to the fragmented condition of modern Christianity. But Kyle helped us see the silver lining of this statement’s dreary facade. Only something of significant and exceptional merit could possess the strength needed to unify so many of God’s seemingly disconnected children.

Kyle eloquently articulated what most Christians, and quite possibly all mankind, surely realize. “After 2000 years Christianity is a complex and sprawling entity. It is more like an urban metropolis than any one person’s home. It is more like a dense 19th-century Russian novel than a crisp Japanese haiku. It is a symphony, not a single note.” In its early life, the Christian faith was propagated through informal accounting. But even as its propagation developed in response to an ever-changing environment it always maintained its “genetic code,” its unique and living essence. An essence so enduring that even after three hundred years, it would not only be present in but also preserved by the Nicene Creed. The reason the Nicene Creed can hold together what Kyle called an “oddly contrasting twenty centuries of Christian history and tradition” is because in its essence it is an articulation of Who Jesus is.

After Jesus’ resurrection, His followers spread the events of His life through oral recountings and letters. These proclamations would eventually develop into missionary preaching, what Kyle called “the liveliest and most original species of theological speech in early Christianity.” Mark 16:20 tells us that Jesus’ disciples “went out and proclaimed everywhere.” The book of Acts gives us five accounts of Peter’s sermons and three of Paul’s. When we examine their preaching closely we find something striking. While their lively and diverse delivery differs based on the speaker, the audience, and the social-historical setting, it remains tied to a dogmatic center. What the early preachers proclaimed consistently includes: Jesus’ incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension as well as the pouring out of the Spirit and how the believers receive salvation. When woven together, the common threads of the apostles’ preaching become the tapestry of what would later become the creeds, what Kyle called “the irreducible core of the gospel on which our salvation depends.” If the disciples’ proclamation is based on historical events or stories, then we might say that the eventual creed is based on the main characters and plot points essential to the story. Change them, and you’re telling a different story. Simply put, to remain faithful to the faith requires a faithful retelling of the story.

Anyone who has ever told a story knows how easily it can lose its meaning when you forget an essential detail. A story can become especially distorted if you misidentify the main characters. Receiving a note passed in school from “Rachel” is more complicated than compelling if there’s more than one “Rachel” in the class. Identifying the right person is important. These potential pitfalls highlight the necessity of a creed. As Christians, we can all tell the same story because the “who” and the “what” are the same. And if, for whatever reason, our telling becomes distorted, we all benefit from corrective instruction.

In our previous post, we referenced Luke 1:3-4 as an example of an early verifiable account of the events of Jesus’ story. This passage is also instructive because its context shows us the progression from proclamation to instruction, the fourth of our seven keywords. Luke indicates that he is writing so that the recipient of his letter, the previously catechized Theophilus, could have the full assurance of what he previously received. Not merely confident in the events, news, or proclamation he had heard but in the formal instruction he had received. This indicates an advancement from the more free but still essentially grounded proclamations of preaching to more formal instruction. At the end of his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul indicates his intention to formally “make known…the gospel which [he] announced to [them].” This is indicative of instruction and bears the early marks of a creed.

In our next post, we’ll continue to advance on our journey. We’ll examine how the usage of “outline” and “confession” in scripture marks the advancement of the Christian faith toward creed. We’ll also look at what happened when someone got the story of Jesus Christ wrong and how this misstep ultimately led to a unifying understanding of Who Jesus is.