As Christian students (CSOC UT Austin), we want to know the incredible history of the Bible.

ENGLISH SPEAKERS TODAY RARELY WORRY ABOUT A BIBLE in their own language. With an abundance of English Bible translations readily accessible, the Bible has become commonplace in the English-speaking world. In fact, there are so many English Bibles available that we may not value the Bible’s preciousness. The availability of the Bible in English, however, was not always the case.

For centuries, English-speakers had no Bible in their own language. In the early fourteenth century, copies of the Bible were extremely rare because they had to be copied by hand, a process that took a significant amount of time to complete. If an English speaker wanted to know about the Bible, that person would have to attend a religious service conducted in Latin by a member of the clergy, who may not have been particularly familiar with the Scriptures. The scarcity of Bibles resulted in a poor biblical education throughout Christendom, even among religious leaders. Furthermore, common people were simply not encouraged to read the Scriptures. Some prominent religious figures even considered it dangerous for the general populace to do so. This situation concerned a number of individuals within the church, one of whom was John Wycliffe.

We owe much to John Wycliffe for challenging this approach toward the Bible. Known as the “Morning Star of the Reformation,” Wycliffe was a pioneering figure who championed the authority of Scripture over all other sources. His retrieval of the belief in sola scriptura—Scripture alone as the ultimate authority—was nothing short of revolutionary in his time.

Born around 1328 in Yorkshire, England, Wycliffe lived in an era when the medieval church wielded immense power, influencing nearly every aspect of society. Educated at Oxford University, he became a master of theology and philosophy, distinguishing himself as a brilliant thinker. Yet, the more he studied, the more troubled he became by what he saw in the church. Clerical corruption, the accumulation of wealth, and an over-reliance on tradition had led the church far from the teachings of the Bible.

Though Wycliffe saw the corruption and shortcomings of the church, he still became a priest and a theologian. As such, he was permitted to read and teach the Bible. Through his reading the Scriptures, he began to realize how crucial they were, not only for clergy but also for common people throughout England. Wycliffe became convinced that Scripture should be the foundation for all matters of faith and practice, a belief that set him at odds with the prevailing view of his day. He argued that the Bible, not the pope or church councils, was the supreme authority for Christians. This conviction was not a mere academic stance; it was deeply personal and practical. Wycliffe believed that every Christian should have access to the Bible, enabling them to understand God’s will directly.

His teaching laid the groundwork for the theological principle of sola scriptura that would later become a cornerstone of the Protestant Reformation. While the idea seems obvious to us today, in Wycliffe’s time, it was a radical challenge to the status quo. The church had long held that its traditions and the pronouncements of its leaders carried equal weight with Scripture, and questioning this hierarchy was a dangerous endeavor.

Despite the risks, Wycliffe persisted. His writings and sermons called believers back to the Word of God, urging them to measure every teaching and practice against the Bible. He inspired a movement of ordinary Christians who sought to reclaim their faith from the grip of institutional control. These early followers of Wycliffe, known as Lollards, played a critical role in spreading his ideas and calling for reform.

One major barrier, however, stood in the way of these groups in need of the Word of God—the Bible was only available in Latin, not English. Although the Bible had originally been written in Hebrew and Greek, it was later translated into Latin and remained in that form until Wycliffe’s day. In the 1300s, few members of the laity (if any) in England could understand Latin. The language had not been spoken there for over 1000 years. English priests and monks had tried to translate the Bible into English before Wycliffe, but none had ever produced a translation of the entire Bible. English speakers desperately needed a Bible that they could understand, and Wycliffe was willing to assume the task.

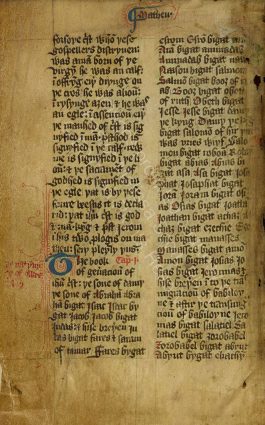

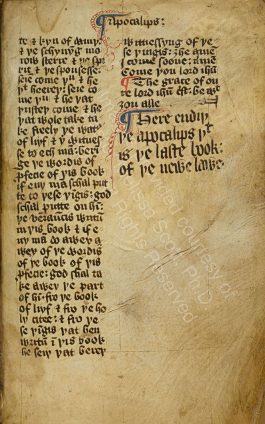

Historical evidence strongly suggests that Wycliffe had been interested in producing an English Bible for some time. Scholars believe that during his career at Oxford University, where he was a professor, Wycliffe probably began gathering necessary reference materials for the translation of the Bible from Latin into English. He may have even prepared an interlinear text for use in the project. It is difficult to say if Wycliffe did any actual translation work and how much, if any, actual translation work Wycliffe did, but it seems that he must at least have been involved with the project as its inspiration and director. He most likely gathered a number of translators together who worked for several years to produce a readable version of the Bible. They finished their earliest version of a translation before Wycliffe died in 1384. Even though copies of the English Bible were extraordinarily difficult to produce, taking almost six months to make a single copy, translators and copiers were desperate to provide the public with a Bible that they could read in their native tongue. Despite the difficulty, so many copies of the Wycliffite Bible were produced that today, that, strikingly, the majority of surviving Medieval English manuscripts in existence are Wycliffite Bibles.

Wycliffe’s life reminds us of the power of Scripture to transform not only individuals but entire communities and eras. His commitment to the authority of God’s Word set the stage for the Reformation, challenging the church to return to its biblical roots. The next time you find yourself asking, “What does the Bible say about that?”, remember the courage and conviction of John Wycliffe. His legacy is a powerful reminder that God’s Word, not human authority or tradition, is the ultimate guide for our lives.

Part 2: From Achievement to Heresy